Words of War: How Language Shapes Propaganda

Insights from a study on linguistic variation of media types in the context of the Russo-Ukrainian war

Following the launch of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, pro-Kremlin propaganda has become more widespread, aiming to legitimize the war through both official state media, such as the press and TV, and social media channels. This has led to an increased interest in designing automatic propaganda and fake news detection tools within the NLP community. Although these methods show promising results, they are mostly based on “black box” transformer architectures, which fail to provide an interpretation of the findings. In other words, one can’t explain why the model decided on whether a certain piece of news is fake or real. In this case, how can we account for the linguistic variation of propagandistic narratives in diverse contexts, such as between state-controlled and social media? One should consider this divergence if they want to tailor a propaganda detection model to a certain media type.

Mobilization vs. Demobilization

In their recent paper “Confuse and Normalise: Authoritarian Propaganda in a High-Choice Media Environment and Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”, M. Alyukov, M. Kunilovskaya, and A. Semenov argue that there is a clear division of labor between state and social media, as these two media types are targeted at different audiences. Since state media consumers are more passive, the government uses a demobilizational strategy to pacify them and reinforce their beliefs, whereas social media propaganda relies on a more mobilizational approach to convince and engage the more active users, intending to prevent them from searching for alternative sources of information. The difference between these two strategies is evidenced by propaganda frames prominent for each media type. For instance, state media aims to normalize the war by downplaying its effects on everyday life in Russia, while social media depicts Ukrainian and Western news as disinformation.

To validate this theory from a linguistic perspective grounded in statistical analysis, I collaborated with Stefania Degaetano-Ortlieb on a project to analyze the divergence between the language of war propaganda on state and social media. For this, we used the Wartime Media Monitor (WarMM-2022) corpus created by the authors of the abovementioned paper, which includes news about the war in Russian media dating from February until September 2022. We applied Kullback-Leibler Divergence (KLD) — a metric comparing probability distributions of linguistic features between two corpora (i.e., how probable it is to encounter one word in one corpus vs. the other) — to detect variations across linguistic levels in the dataset. As our linguistic features, we selected content words, such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and proper nouns. The formula to calculate the KLD of the language of state media (State) given that of social media (Social) would be the following:

To visualize our results, we produced these word clouds, showing the most distinctive words for each media type (social media on the left, state media on the right):

By analyzing these word clouds, we could clearly see a division between the mobilizing character of social media language and the demobilizational narratives on state media. For instance, the word war — which appears in the middle of the word cloud on the left — is the most distinctive word for social media. This is not surprising, as this term was banned in Russian official media to refer to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which has instead relied on euphemisms. We can observe them by looking at the state media word cloud: words like special and military form part of the newly-coined term special military operation; the word situation can also be used as a replacement for “war” (e.g., situation in Ukraine). These, however, are the only words that refer to the topic of war, even if indirectly, in the state media word cloud. In contrast, there are many more words distinctive for social media related to the military and fighting (front, army, soldier, to fight, an abbreviation of Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, to kill, etc.). Their high contribution to the social media language, together with direct war terminology, points to the government’s efforts to mobilize the population and encourage it to fight against Ukraine, while state media employs the normalization frame by avoiding mentioning the war.

Apart from that, words like propaganda, truth, and fable that are prominent on social media might indicate the disinformation frame with its mobilizational character, which is common for this media type. At the same time, state media language is highly characterized by the names of geographical entities, specifically Ukrainian territories that are or were occupied by Russia: Donbas, DPR (an abbreviation of Donetsk People’s Republic), LPR (an abbreviation of Luhansk People’s Republic)1, Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson [Oblasts], as well as administrative units such as republic and oblast. Moreover, the words referendum, voting, and to vote, which are probably mentioned in the context of sham referendums conducted in September 2022 on Russian-occupied Ukrainian territories about joining Russia, are also distinctive for state media language. All of this might be part of territorial control propaganda: by talking about these regions and referendums, the Kremlin attempts to establish its authority over them and create an illusion that it has already achieved its military goals, thus normalizing the war even further.

An interesting observation is that two distinct words that would be both translated as “Russian” into English are visible in the word clouds: the word русский (transcribed as russkiy) refers to the Russian ethnicity and is distinctive for the language of social media, while the word российский (rossiyskiy) is used to indicate the Russian nationality or citizenship and is more characteristic of the state media language. The word русский is especially frequent as part of the phrase the Russian world — a concept promoting a shared cultural and political space among Russian speakers, often used to justify Russia’s influence over post-Soviet states. Therefore, using this word has a more mobilizing character, as it appeals to ethnic Russians and urges them to fight against a common enemy, while employing the word российский is aimed at unifying the Russian population under an authoritarian regime. In a similar vein, we can see words like Denazification2 and enemy in the social media word cloud, whereas safety and protection have a high contribution to the state media language, making the distinction between mobilization and demobilization strategies on these media types even more salient.

Beyond Words

When looking at the word cloud for social media, we saw some unexpected results. Some words just didn’t make sense, since they were rare, or it wasn’t clear why they would be distinctive for social media. One of them, смолодить (smolodit’) was a non-existent word resulting from an error in automatic part-of-speech tagging during the pre-processing stage, and it came from the word смолоду (smolodu), meaning from a young age; another example is the archaic word снову (snovu), which means again. To find out why this was the case, we searched for these words in the corpus to see their surrounding context. It turned out that the posts where these words appeared were duplicated multiple times. The high frequency of these words likely inflated their KLD values, explaining their apparent prominence. What we couldn’t explain, however, was the fact that we had accounted for duplicates by applying a script that would automatically remove them before running the experiments. The script seemed to have worked at first, as it deleted a lot of duplicates — but why not all of them?

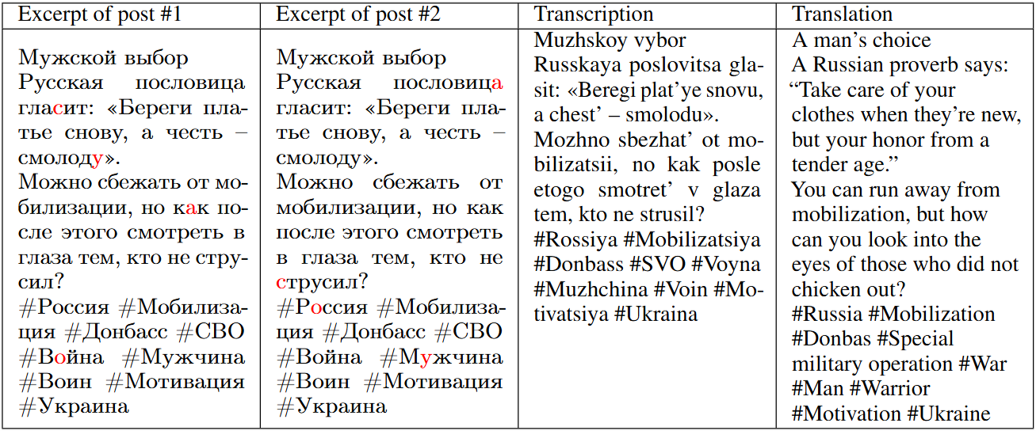

The answer is simple: homoglyphs. These are characters originating from different scripts that look identical. Compare, for instance, Cyrillic letters “а”, “о”, “у”, and “с” with Latin characters “a”, “o”, “y”, and “c”. To a human eye, they look the same, but a computer program designed simply to match words of two different texts wouldn’t be able to distinguish between them. Consider the following example of a duplicated post (which, by the way, also exhibits a mobilizing character of social media language, as it literally talks about mobilization):

The homoglyphs (Latin letters instead of Cyrillic ones) are highlighted in red. As can be seen, the two words mentioned above (снову and смолоду) appear in this post. Also, the homoglyphs are inserted in different words of the same text, and that’s why our script failed to detect them. But why would anyone want to use them?

Homoglyphs are a common strategy to avoid plagiarism detection and conduct phishing attacks. In this case, however, they are employed with a different purpose. As we know, many social media platforms have filters that automatically detect and block duplicate content to prevent the spread of disinformation. Could it be that homoglyphs were inserted in this and similar posts to bypass those filters? We cannot say for sure, but since they affected our KLD results, we believe this could be another propaganda strategy, which is achieved not by manipulating the language but by relying on extralinguistic factors.

In conclusion, the language of propaganda can be construed in many ways, and it adapts to the contextual situation, such as different media types. Studying this variation is crucial to improving automatic disinformation detection. Moreover, we should always keep our minds open to unexpected findings, which can lead to discoveries outside the scope of our research.

DPR and LPR are self-proclaimed, Russian-backed territories in eastern Ukraine that were recognized by Russia in 2022 and later used to justify the annexation of parts of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts.

A term used as a justification for the invasion, stemming from the narrative that Ukraine is ruled by Nazis.